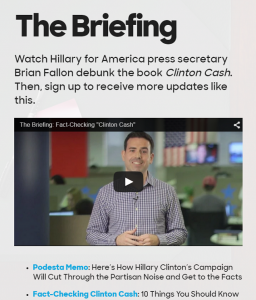

Editor’s Note – When the NY Times broke the story about Peter Schweizer’s book entitled ‘Clinton Cash,’ the attacks came immediately from The Clinton camp. Their talking points were flying fast and furiously and many asked how they knew what was in the book when it had not been released in full.

The answer – the Clinton camp had purloined a copy somehow, very early on, and Schweizer knew it. Despite this, the story did not fizzle and even with their web site “The Briefing,” sporting a video attempting to ‘debunk’ the book by Press Secretary Peter Fallon, it is still growing in intensity.

It should grow; if any other person or couple had even the appearance of doing one tenth of what the Clinton’s and their foundation did, every single media outlet would have run already forced a candidate to drop their campaign. Remember Gary Hart and Donna Rice from 1987? That was just an affair and many think his fall from grace was the beginning of the end of civil politics, the “week politics went tabloid.”

Of course with the Clintons, “…there is one set of rules for politics, and another set for real life, you just have to learn to deal with it…”

Now America is dealing with it, but like Bill O’Reilly, we think the FBI must open an investigation. America deserves better, and deserves the truth. We are not going to get it from the media, and the Clintons know it – so does their staff in the ‘war room.’

Inside the ‘Clinton Cash’ war room

How Hillary’s team worked furiously to attack, undermine and debunk the book that threatened to disrupt her campaign.

By Annie Karni – Politico

In early March, weeks before Hillary Clinton even announced her campaign, spokesman Brian Fallon and research director Tony Carrk began holding regular war room meetings with a team of eight volunteers on a serious mission: Fighting back against a forthcoming book, “Clinton Cash,” that threatened to seriously disrupt the campaign in its infancy.

This was an updated version of the famed war room that fought the first round of Clinton scandals in 1992, propelling Bill Clinton to the presidency; now, two months later, aides point to the handling of the “Clinton Cash” threat – a still-unfolding stream of allegations involving the Clinton Foundation and its donors, but one that seems not to have seriously altered perceptions of Hillary – as proof of the campaign’s ability to manage messaging and counter the inevitable blowback of an 18-month campaign.

The campaign systematically raised questions about the objectivity of author Peter Schweizer and, according to sources with knowledge of the deals, strategically leaked details of the book to news outlets to undercut the exclusivity of excerpts given to reporters at The New York Times and Washington Post, who had obtained special deals with Schweizer.

Sources close to Clinton described meetings at her personal office in Midtown Manhattan that were so focused that when Fallon’s twins were born April 8 — four days before Clinton officially launched her campaign — he continued to join the conferences by phone from the hospital in Washington, D.C., despite being on leave.

The game plan at first was two-pronged: debunk author Peter Schweizer by stressing his ties to Republicans and his close friendship with the Koch brothers, while a second group of research and communications operatives pushed positive messages the campaign would roll out while the book was making headlines.

Instead of hunkering down, Clinton would make news herself with a speech on criminal justice — where she called for an end to mass incarcerations — and a newsy speech on immigration, where she vowed to expand on President Obama’s executive actions to include another 5 million undocumented immigrants from deportation.

Behind the scenes, the strategy turned from defense to offense in late April, when the campaign caught a break and obtained an early copy of the 256-page book.

Behind the scenes, the strategy turned from defense to offense in late April, when the campaign caught a break and obtained an early copy of the 256-page book.

At that point, the campaign began pitching its own stories about “Clinton Cash,” and then finally turned to new media to tell its own version of the story.

Campaign operatives leaked single chapters of the book to national media outlets, sources with knowledge of the deals said — a strategy that allowed them to undercut the reporters who, through exclusive agreements with Schweizer, had obtained early copies of the entire tome, and also to attack the content at the same time.

Schweizer, in an interview, said he was aware of the strategy.

“I knew fairly early on they had access to the book,” he said. “Sure, it helped them. They’re famous for that. I was aware they were leaking selectively chapters, particularly as journalists who had access to the full book had contacted them with questions. They didn’t want to share the complete book, just chapters. For me, the power of the book is in the pattern of the behavior.”

Schweizer said he caught on to the strategy when the New York Times investigative team was working on a 4,000-word story about the connection between Clinton donor Frank Giustra and the approval of a sale of a mining company to Russia, which drew from chapters 2 and 3 of his book.

Indeed, the Clinton team was particularly concerned that the Times and Post would use his book as a jumping off point for investigations — coverage that would make it harder for them to simply dismiss Schweizer as a tool of the right.

Just as the New York Times was preparing to publish its investigation of the Giustra matter, “the Clinton team is sending chapter 3 of the book to Time magazine and other reporters,” Schweizer said. “Who gets just one chapter of the book?

They gave them chapter 3 but not chapter 2, which is also on the uranium deal. You’ve got reporters running with stories that didn’t have the full picture. That was the Clinton strategy: to muddy the waters and not have an honest conversation.”

The campaign says that Giustra, the Canadian billionaire whose role in the uranium deal is outlined in chapter 3, sold his stock two years before Clinton was appointed as Secretary of State. Schweizer says that’s only part of the story. “The book talks about nine people who are shareholders, not just Giustra,” he said. “They never mentioned the other eight. They’re mentioned in chapter 2, not 3.”

The goal of aggressively parceling out parts of the book was to generate headlines that could be discredited before the book hit the shelves and before Schweizer went on the television circuit promoting his work.

When Schweizer started making the media rounds on the Sunday shows ahead of the May 5 book release, the Clinton team had managed to get ahead of him to put him on the defensive. “We’ve done investigative work here at ABC News, found no proof of any kind of direct action,” “This Week” host George Stephanopoulos said of the claims about the uranium deal with Russia.

Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta and Fallon published their own posts directly to Medium, to point out what they said were errors and omissions.

DONATING MILLIONS Former President Bill Clinton with Sir Tom Hunter, left, and Frank Giustra, major donors to Mr. Clinton’s charitable foundation – NY Times

During the weeks that various chapters of the book were making headlines, the campaign began releasing nightly memos to surrogates and supporters with stories and commentators on air who had discredited the book, or raised questions about the reporting. In total, the campaign put out five detailed memos to its network.

“In the last two days alone, three new claims by the partisan author of the Clinton Cash book have been discredited by independent news outlets,” read a line in one of the memos.

The final push came on the day of the book’s release. The campaign spent over 96 hours building out “The Briefing,” a website that launched on the day of the book’s release, which included an upbeat video featuring Fallon responding to the book and a supercut of Clinton surrogates and talking heads with the general message: “there’s no there there.”

In the donor world, the painstaking strategy to deal with the book was noticed.

“The campaign didn’t get paralyzed,” said Tom Nides, a vice chairman at Morgan Stanley and a close Clinton confidant who is her main liaison to Wall Street. “They didn’t get in a bunker, they kept supporters up to date daily— it felt very proactive.”

And perhaps most important to the donor class who may have harbored fears about Clinton’s weaknesses on display so early in the campaign, the candidate herself appeared relaxed and confident as she attended fundraisers in Washington and New York City.

“This could have gotten nutty,” Nides admitted. “She herself was a more relaxed Hillary. I’ve gotten universal feedback from these meetings that she’s excited to be there, she hung around. She was supposed to be at the event for an hour-and-a-half, she stayed for almost two hours. She didn’t act like she had to get back to the bunker. She was upbeat, positive, and not defensive. People tee off of that.”

So far, Clinton herself has answered only one question about the book, without referring to it by name. At a campaign stop in New Hampshire last month, she dismissed it and said she expected to be “subject to all kinds of distractions and attacks.” She has not addressed it publicly since then.

But that doesn’t mean it hasn’t been on the minds of the staffers and volunteers who manned the war room. As Clinton was speaking about immigration reform at a high school in Las Vegas on Tuesday, her campaign operatives back in Brooklyn waited eagerly on the results of a new poll.

When The New York Times poll popped, showing Clinton’s favorability had risen over the past year, the team from the war room finally exhaled.

“Clinton Cash,” the poll showed, had not had the devastating impact the campaign had feared. After weeks of stories pegged to chapters in the book, only 10 percent of voters said they believed foreign donations affected Clinton’s decisions as secretary of state, according to the poll, and more voters said they saw Clinton as a strong leader than they did earlier in the year.

But Schweizer notes that the themes of the book have now become a part of the Clinton narrative, and could easily pop up later in the campaign — especially as news organizations continue to plumb the Clinton Foundation and its donors.

“I think they have done a very detailed and aggressive campaign to try to undermine the credibility of the book,” Schweizer said. But he pointed to polls showing a relatively high percentage of voters questioning her trustworthiness.

“The narrative is now framed around the foundation and Bill’s speeches, and what role did that have on her decisions at the State Department,” Schweizer said. “My sense is those questions are going to be asked whenever she decides to actually talk to the press.”