John Kerry’s secretary of state dry run

By JESSICA MEYERS – Politico

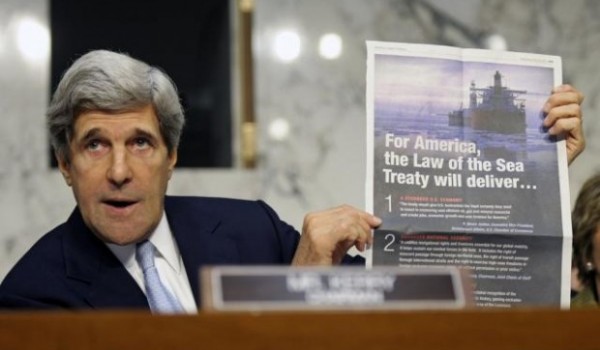

Sen. John Kerry has the perfect audition piece for the secretary of state job he appears to covet — the long-stalled Law of the Sea treaty.

He’s come armed with a throng of industry backers and pleas from the country’s top officials. But a cadre of conservatives remains determined to sink it.

The international treaty, which governs use of the world’s oceans and affects everyone from shippers to telecom companies, has withered in the Senate for almost two decades. If Kerry fails to slip it through this session, the Foreign Relations Committee chairman doesn’t just miss out on the lead role. He loses treaty supporter and Foreign Relations Committee ranking member Dick Lugar (R-Ind.), along with other willing moderates.

So he’s positioning the vote for the lame-duck session, when it stands the best chance. And with Congress at an impasse, nothing will look better than a Senate treaty that doesn’t need House support.

“I refuse to politicize this,” Kerry told POLITICO, “so we’re not going to do anything until after the elections.”

The debate comes down to sovereignty and money. Advocates argue the treaty would allow the United States to play a greater role in maritime decisions and enhance both business opportunities and navigational rights. Opponents say it robs America of its authority and redistributes revenue to developing countries.

Kerry said lawmakers need to revisit the treaty because the United States abides by its rules but can’t benefit from them. This matters even more as countries lay claim to the melting Arctic’s routes and resources. The Massachusetts Democrat points to “significant backing” from oil and gas companies, the Navy and the maritime industry.

Kerry’s critics consider the recent push as much about politics as principle. His desire for the Cabinet position is one of Washington’s badly kept secrets.

“He’s very well versed in the issue, and he’s decided that it’s doable, and if he gets it across the finish line, maybe he will get secretary of state,” a senior GOP aide said.

A letter signed so far by 28 senators, including five Foreign Relations Committee members and Minority Whip Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.) promises to oppose ratification.

The treaty “reflects political, economic and ideological assumptions which are inconsistent with American values,” the senators wrote.

The European Union and 161 countries have signed the treaty, known as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The United States remains the primary industrialized nation not to have done so.

The Foreign Relations Committee will hold its fourth hearing Thursday, this time focusing on the treaty’s effect on business interests.

Industry may end up creating some of the most powerful waves. Lockheed Martin, Verizon, the Chamber of Commerce and a host of commercial heavy hitters are lobbying for passage. The American Petroleum Institute joined a list of supporters last week, and both the National Association of Manufacturers and the Association for Rare Earth added their names Monday. Groups united earlier this year to create the American Sovereignty Campaign, which focuses solely on promoting the treaty.

“Before it was all government-to-government stuff, but industry is actually suffering and speaking up for the first time,” said Jonathan Waldron, a maritime lawyer. “This is probably the first time ever that industry has gotten involved.”

Companies now have the capability to mine minerals and lay underwater cables deep in the world’s oceans, he said, affecting everything from cellphones to gas prices. Waldron said the treaty would enhance these opportunities by solidifying the country’s rights further from shore.

Chamber of Shipping of America President Joseph Cox, who testified in favor of the treaty twice in the past two decades, said the new interest could shift the dynamic.

“I’ve been at the table, the Navy has been at the table and everyone has patted our head and told us to go home,” he said. “But now we have the money guys involved.”

A high-profile cast including six four-star generals and admirals, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta, Joint Chiefs of Staff head Martin Dempsey and John Negroponte, the first director of national intelligence, have testified in agreement.

“We have undermined our moral authority by not having a seat at the table for nations who make arguments,” Panetta said at a recent hearing, citing concerns with China’s claims in the South China Sea.

Detractors say the current law works just fine.

“It would literally be crazy for us to turn over our sovereign rights of our continental shelf to an international body and expect that everyone else is going to play by the rules,” Sen. Jim DeMint (R-S.C.) told POLITICO.

Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld testified against the treaty on similar grounds. “I do not believe the United States should endorse a treaty that makes it a legal obligation for productive countries to pay royalties to less productive countries,” he said at a recent hearing.

The financing refers to payments of up to 7 percent that the United States would need to make. Clinton has said there would be a say in how that money gets distributed.

So what’s new in a fight that started after the Convention formed in 1982?

“Nothing,” said Steven Groves of The Heritage Foundation, who has testified against the treaty and doesn’t find the industry backing all that revelatory.

Except, he said, Kerry “may see that it’s becoming more and more difficult to get the votes he needs.”