Editor’s Note: From our great friend Dr. Lawrence Sellin, Phd. Dr. Sellin is also a retired colonel with 29 years of service in the US Army Reserve and a veteran of Afghanistan and Iraq.

Why Pakistan wants the US to lose in Afghanistan

Pakistan sees China, not the United States, as its long-term strategic partner.

Pakistan has always viewed Afghanistan as a client state, a security buffer against what they consider potential Indian encirclement and as a springboard to extend their own influence into the resource-rich areas of Central Asia.

Now Pakistan has significant economic incentive to exclude western countries from maintaining any influence in Afghanistan.

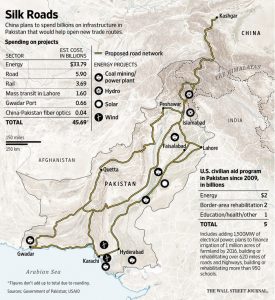

It is called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which is part of China’s larger Belt and Road Initiative that aims to connect Asia through land-based and maritime economic zones.

CPEC is an infrastructure project, the backbone of which is a transportation network connecting China to the Pakistani seaports of Gwadar and Karachi located on the Arabian Sea. That network will be coupled to special economic zones and energy projects, the latter to help alleviate Pakistan’s chronic energy shortages.

As noted by Forbes, “For Pakistan it’s a big infrastructure project, which could help the country make a big step forward, from emerging to a mature economy. For China, CPEC is the western route to the Middle East oil, and the riches of its ‘third continent,’ Africa. It also serves Beijing’s strategic ambition to encircle India, something that makes Pakistan a natural ally.”

An extension of CPEC to Afghanistan would benefit both China and Pakistan, whose economic goals include exploiting the estimated $3 trillion in untapped Afghan mineral resources. The withdrawal of the U.S. and NATO from Afghanistan would allow China to reap rewards from the reconstruction of the war-torn country, possibly as a quid pro quo for mining rights.

Islamic militancy has long been one element of Pakistan’s foreign policy. As early as the 1950s, it began inserting Islamists associated with the Pakistan-based Jamaat-e-Islami into Afghanistan.

In 1974, then Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto set up a cell within Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI) to begin managing dissident Islamists in Afghanistan. Pakistani President Zia ul-Haq (1977-1988) once told one of his generals: “Afghanistan must be made to boil at the right temperature.”

Pakistan’s present support for the Taliban is just a recent iteration of a long-held policy to influence or destabilize Afghanistan. The use of instability may have served its interests in the past, but Pakistan is holding the Islamist tiger by the tail.

It is not clear that a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan would cooperate in fulfilling Pakistan’s or China’s international plans or, more broadly, hinder them simply by providing a Petri dish for instability. During the period in the 1990s when the Taliban ruled Afghanistan, they three times thwarted one of Pakistan’s key foreign policy objectives, to recognize the Durand Line as the permanent border between the countries.

The success of the CPEC project depends on the stability of Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest province, where the CPEC ports of Gwadar and Karachi are located.

It is an ethnically mixed transnational region spanning southwestern Pakistan, eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan, where the Baloch people and the Pashtuns constitute the majority of the population, while the remainder comprises smaller communities of Brahui, Hazaras, Sindhis and Punjabis.

Since 1948, Balochistan has been the home of a festering insurgency waged by Baloch nationalists against the governments of Pakistan and Iran.

Pakistan may someday regret using the Taliban as an instrument of its foreign policy. Stability is a prerequisite for successful economic develop and it is a more difficult condition to create than instability.

Those who live by insurgency can also die by insurgency. Pakistan would do well to remember that.

We’re watching…and listening…everywhere…for a reason.